How an LA Community is Radicalizing Traditional Latinx Genres

This article originally appeared in the print version of She Shreds Magazine Issue #16, which was released in December 2018.

From cumbia to corridos, every Latinx genre is entwined with movement, often caused by sorrow, joy, or acts of transgression (and sometimes, all three at once). For instance, Colombia’s indigenous and African communities comprised the roots of cumbia, and its guacharacas, gaita flutes, and distinctive 2/4 hand drum rhythm; in the 1940s and 1950s, big bands’ interpretations of cumbia songs helped propel their popularity worldwide. The aching balladry of boleros, which can be traced back to 19th century Cuba, won over Mexican audiences around the mid-20th century as well. The Mexican Revolution gave way to rancheras, emotive takes on folk songs that originated around the ranches of Mexico. Much like the universe we live in, the scope of genres within Latinx music continues to expand and redefine itself in real time. Today, a burgeoning community of forward-thinking Latinx artists in Los Angeles—including San Cha, Sister Mantos, Gemma Castro, and Te Adoro—are both radicalizing and evolving the musical disciplines that have been central to their family histories, and in turn, developing as artists and human beings.

San Cha

Several years ago, the singer-songwriter San Cha found herself targeted by accusations that she was a witch. It was October, and San Cha had arrived in Jalostotitlán, Jalisco, Mexico amidst a time of religious observance when the town took a statue of the Virgen Maria to “tour” every farm. “I’m over here with no eyebrows, purple hair, all of my clothes are see-through, or really long and scary,” San Cha laughs. “And everyone was telling my cousins that I was a witch because I don’t take communion! It was so intense.” Couple that with the fact that San Cha—who, at the time, had left the Bay Area during a period of personal and professional tumult—took up with her Tía Luz, a woman living alone on a farm with, yes, two black kittens. “I was the town witch for a little bit,” she says. “I’ll take it. I love that a girl can be by herself.”

San Cha, who came up in the underground music scene in the Bay Area, where she performed at queer and goth parties both solo and with her band Daddie$ Pla$tik, suddenly had time to delve into music sans distraction. One of those projects involved recording ranchera tunes that she’d grown up with, which she then recorded on CDs and gave to her family members. One of those songs, “Ya Se Esta Llegando La Hora,” is especially dear to San Cha and her family, as her grandmother and sister would sing it together as a duet. But she put her own spin on these living versions of her family’s history. “I would do, ‘Por Un Amor’ and ‘Déjame Llorar,’ [but] the instrumental parts I would copy with the synths,” she says. “And even ‘Por Un Amor,’ I just did the mariachi part and layered myself over and over and did harmonies.” The approach at once delighted and puzzled her family. “My tías were like, ‘That’s not you, what mariachis did you get to sing that?’” she remembers. “And I was like, ‘Girl, I can sound like a man.’”

Belting rancheras evolved into its own kind of power, which San Cha harnessed during a stint singing on Mexico City’s streets with her then-neighbor. “Singing on the street… there was a thing that clicked, where I was like, ‘Oh, this is the freest you’ve ever felt,’” she says. “Belting something really loud does something to your body.” There, she had the idea to make an album deeply layered with backing vocals and harmonies, as well as cumbia rhythms. That eventually became Capricho Del Diablo, culled from the nine demos she wrote and recorded at her tía’s house. It’s rooted in cumbia, and also evolves traditional conceptions of the very rancheras and boleros that she grew up listening to, such as “Historia de Un Amor.”

San Cha decamped to Los Angeles in 2015, and set about re-envisioning the demos with other musicians, some of whom are in the psychedelic project Sister Mantos. On the album, San Cha also flexes her pop sensibilities, which stem from her early days loving and listening to the Chicana pop star Selena, and watching the performative prowess of Gloria Trevi onscreen. It also bears the impact of her time singing in the church, where Lent season’s sad songs were her favorite. “I’ve always been drawn to minor chords, and songs of longing,” she says. In a similar vein, Capricho Del Diablo also became a conduit through which San Cha processed her fraught experiences. “Writing the album, I was like, ‘Okay, these people hurt me, but I love these people. What things do I want out of relationships and what kinds of power dynamics should I be avoiding? And what kind of relationships do I care for and want to keep nurturing?’”

Sister Mantos

The multi-instrumentalist Oscar Santos is the founder of the amorphous project Sister Mantos, whose current incarnation includes 11 musicians who collaboratively write songs together. As a baby, Santos fled with their parents from their native El Salvador in the 1980s. Upon arriving in the San Fernando Valley, in North Hollywood, the Santoses lived with family who’d already arrived. There, they were first exposed to the United States pop mainstream. (Santos’ aunt, who was a teenager at the time, jammed to the likes of Boy George, Wham!, and Cyndi Lauper.)

As a child, Santos remembers being surrounded by classical music and boleros via their grandfather, too, but found more resonance with Latinx genres later on in life. In part, this was due to circumstance. “I grew up in a Latin household but my parents didn’t really listen to that much Latin music. And that’s one of the things I think about, and I’ve actually been talking to friends about it who are also Salvadoran: some Salvadoran parents, when they came here, didn’t have much of a chance to bring things with them,” Santos says. “It was like, ‘get the fuck out,’ because the civil war was so crazy. My parents would play it, but they didn’t come with their record collection.”

Santos, though admittedly a shy young person, always had a desire to entertain—they would lip-sync pop songs at shows they’d put on for family by the fireplace. In high school, they became part of a thriving scene clustered around the performing arts theater Raven Playhouse (situated next door to the original DIY haunt, The Smell) that let high school bands perform on weekends. “We were on some shit that I think now is really resonating with people,” Santos says. “Everyone’s been hungry for that for so long. We were doing that: making psychedelic music, Spanish rock music, canciones inspired by that, but also The Cure and Depeche Mode. Everyone was into new wave and ‘80s, but also singing in Spanish.”

Since then, Santos has never not been in a band. The Sister Mantos project began as a solo effort, a way to explore and learn computer music, that also coincided with the Myspace era. Online, Santos began to meet people, and even took a risk (that paid off) playing a festival in Europe when Sister Mantos was barely nascent. After several years of honing their skills performing and mixing, they released UNK, an album reverberating with textured, psychedelic dance gems. It stemmed from a simultaneous desire to sing more in Spanish and to apply Latin beats to the music, with horns, vocals, and other contributions from the incredible community of artists currently revolving around Los Angeles (San Cha and Sister Mantos share band members, and the band has played shows with Gemma Castro and Te Adoro). Rhythmically, it’s centered by Santos’ college studies in traditional Afro-Cuban percussion, found in the likes of worship tunes such as orishas, along with funk comps and the stylings of Parliament, and spatial sounds by tropicalia artists.

Lyrically, Sister Mantos centers questions of identity and fluidity. “The musicians I play with are immigrants, or children of immigrants, or have a relationship to a critical look at the United States. We are all thinking about that thing: ‘Do we belong to this country that doesn’t want us? But we do belong to our home lands that we’ve never been to?’” It’s also why the Sister Mantos insignia can often be found inside an alien head logo. “One of the things that runs through for us is this identity as an alien,” Santos says. “From age two to 10 or 11, I was literally an alien until I became a resident.” The sense of otherworldliness and outsiderness has taken on even greater weight, too. “It applies to us more widely, because many members of the band now identify as queer or some part of the umbrella of the LGBTQIA+ community.”

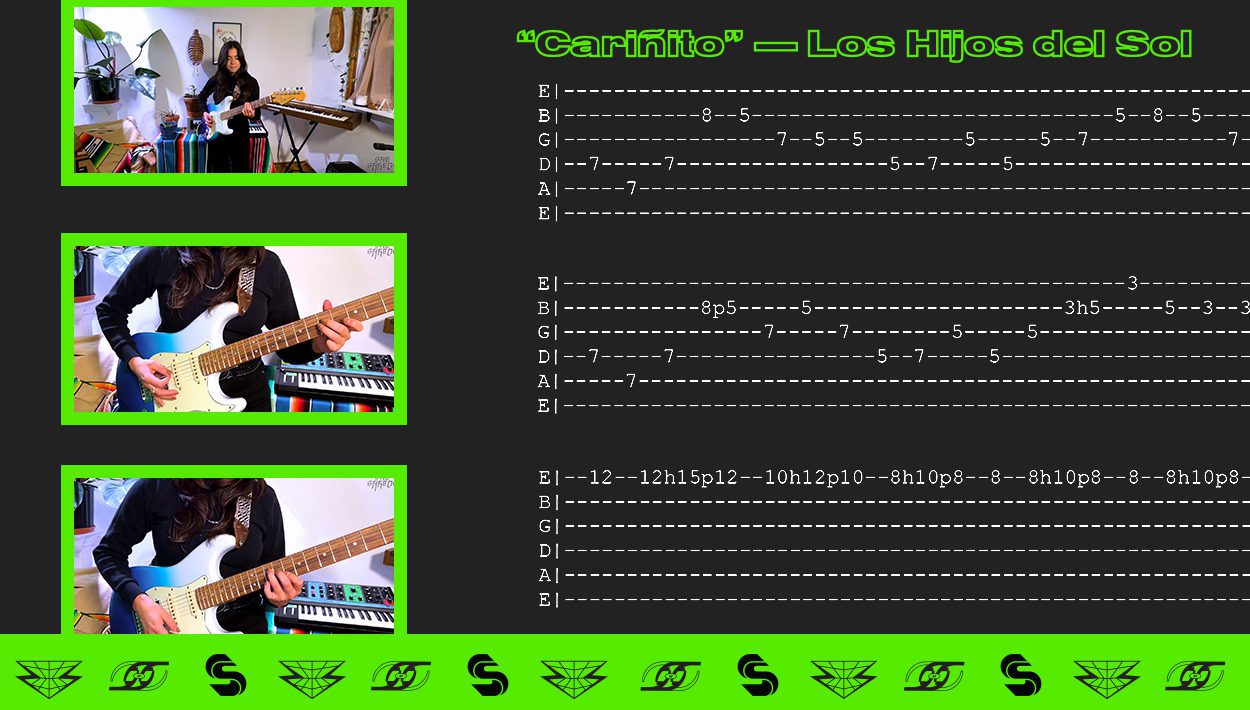

Gemma Castro

For the vocalist and songwriter Gemma Castro, the sounds of footsteps, ringing phones, and doors opening and closing aren’t just innocuous noises; they’re part of a symphony that invites narrative interpretations. Capturing ambient sounds and field recordings is crucial to her cinematic music, which she writes and records at her home in Los Angeles. “I started recording and experimenting with sounds,” Castro says. “I’d be in the kitchen recording my mom washing the dishes, and use it to make a beat . I’ve always been interested in the organic, and reflecting the environment of where I’m at. There’s something very true about that.”

Castro grew up in Lakewood, a suburb of Los Angeles, in a Mexican household. (Her mother is from Guadalajara, while her father hails from Zacatecas.) Growing up, in their living room, she and her family would listen to banda, tamborazos, and corridos, and especially artists including Vicente Fernandez. Her mom, who was especially fond of bolero and mariachi songs, and musica romantica, would invite artists to come perform at their house. Castro says she felt particularly drawn to boleros and jazz music. “I did look up to Eydie Gormé’s stuff and thought, ‘Oh yeah, I can do something like that,’” she says. “I always thought about doing something like Mercedes Sosa and Violeta Parra, because I loved how they would celebrate the beauty of life, and talk about helping people and using music as a vehicle to make change.”

As a child, Castro recalls lining up her stuffed animals in her room and putting on concerts for them. Later on, she would lead the choir in church, and took up playing the piano at home. “I felt amazing and special when I would do those concerts in my room,” she says. “I just believed in my voice, and always felt really confident about that. I was a very introverted, quiet person, but that was the thing that I felt no one could ever take away from me or deny. I felt really free and accepting of who I was when I was doing that.”

On her Gemma EP, released in 2016, Castro channels her affinity for stark songwriting akin to that of Chavela Vargas, melding that with her interest in crafting electronic soundscapes and jazz-inflected vocals to make something transformative. This instinct transports the listener to where she’s been; for example, on “Stranger,” when you hear her mom calling at her, in Spanish, to answer the phone. It also makes a particularly knotty moment, a reflection on someone leaving for good, feel all the more visceral on the gorgeous “Tu Me Acostumbraste.” “It’s someone leaving and they’re getting in the car and driving away, and now you’re just like, ‘Fuck. I have to go on, having already been used to you being here. Now I have to exist in my world,’” she says. “So I really tried to make those [situations] real, like a movie.”

Her latest track, “Sirena,” sounds at once like a meditation and a call from beyond; it’s drawn from a body of new music that Castro is working on, which she says “is stretching itself into new places… in all directions. Slower, faster, bigger, smaller.” It’s all in the service of a larger idea: “Accepting wherever you’re at right now,” she says. “Doing what we can at this time, and being gentle with ourselves.”

Comments

[…] Listen to “Levanta Dolores” available now on Spotify, Bandcamp and Apple Music, and read more about San Cha and the latinx community radicalizing traditional latinx genres. […]

Pingback by She Shreds Media on June 16, 2020 at 4:42 pmThe Latinx music industry has long been a place of radicalism, where artists are always pushing the boundaries of what is allowed to be said and done. But now, as the industry has grown, so has its reliance on traditional Latinx genres. I will have to visit https://www.careersbooster.com/our-services/cv-editing/ website for help in my essay. In recent years, the Latinx music industry has become more homogenized than ever before. An endless stream of pop-infused bachata and reggaeton is released each year by artists who are often pressured to toe a certain line in order to be successful.

Comment by Kate John on October 24, 2022 at 10:44 pm